Joyce Jones remembers a former colleague who talked about wanting to travel to Europe to see the places where her ancestors came from.

“Don’t you have that desire?” Joyce recalled her co-worker’s question. “She was clueless to the fact that my ancestors were not from Europe, number one. And number two, there’s going to be a certain point that I can go back to, but especially in those days, it was next to impossible” as an African American to fully research her ancestry.

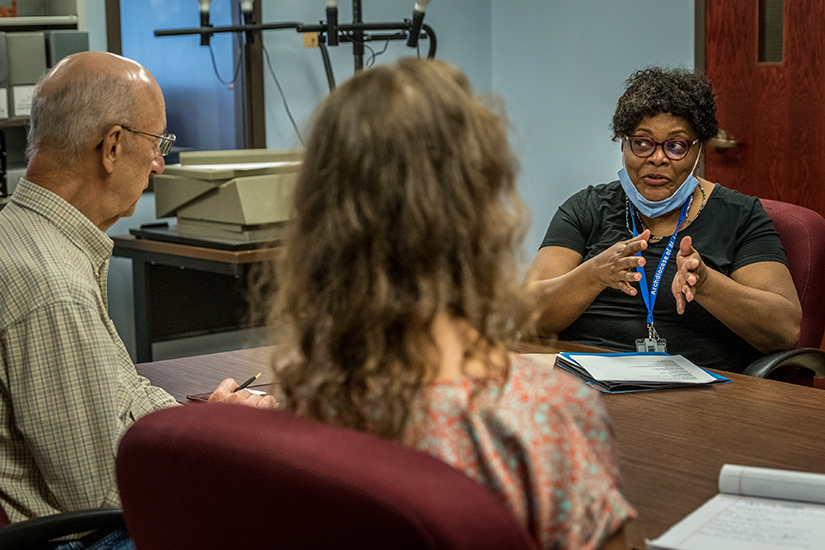

Joyce Jones, right, director of the Office of Racial Harmony, met in 2021 with volunteer researcher Emory Webre and archivist Rena Schergen to discuss their research of people who were enslaved by bishops and clergy in the Archdiocese of St. Louis. Photo Credit: Lisa JohnstonJoyce has reflected on that memory in the midst of her research into the Church’s involvement with the institution of slavery. In 2018, the archdiocesan Office of Archives and Records began researching the archdiocese’s involvement in the institution of slavery. The project was formally named “Forgive Us Our Trespasses” in 2021.

Joyce Jones, right, director of the Office of Racial Harmony, met in 2021 with volunteer researcher Emory Webre and archivist Rena Schergen to discuss their research of people who were enslaved by bishops and clergy in the Archdiocese of St. Louis. Photo Credit: Lisa JohnstonJoyce has reflected on that memory in the midst of her research into the Church’s involvement with the institution of slavery. In 2018, the archdiocesan Office of Archives and Records began researching the archdiocese’s involvement in the institution of slavery. The project was formally named “Forgive Us Our Trespasses” in 2021.

The effort acknowledges that a wrong was done, said Joyce, who directs the archdiocese’s Office of Racial Harmony and is a member of the committee overseeing the research project.

“When you talk about enslavement, there was a period of time in the Catholic Church where our leaders thought of African Americans as less than human,” she said. “Granted, there were people who were against racism, against slavery, but time after time, you see documentation where archbishops and priests were OK with it. This acknowledges that — for whatever they thought during that time period — it was wrong.”

The research has been a slow, but steady process. Much of the work has involved poring through financial ledgers and written correspondence. There are no ancestry websites to comb through. Details have to be pieced together. And the details that have been discovered often leave more questions than answers.

It’s a stark reminder that the God-given human dignity of enslaved people was not valued, Joyce said. “You’ve heard of the 1870 wall, right? From 1870 going forward, census takers had to put names in their records. Prior to that, enslaved people were just labeled male or female, and their age, or approximate age.”

Joyce hasn’t researched her own family’s ancestry. “I don’t want to be disappointed,” she said. “People don’t understand the trauma of knowing that other people can search their family histories — it has gotten easier for people of African descent, but it’s a lot of work.”

“Waiting for someone to tell their stories”

Eliza "Liza" Nebbit (sometimes spelled Nibbit or Nesbit) was transferred by Bishop Louis William Valentine DuBourg to St. Rose Philippine Duchesne and the Religious of the Sacred Heart.Photo Credit: Photo courtesy of Society of the Sacred Heart, United States – Canada ProvinceNot much is known about Harry and Jenny. Their last name is listed in records with several variations: Nebbit, Nibbit and Nesbit. But what is known is that the couple, who were enslaved for much of their lives, was purchased by Bishop Louis William Valentine DuBourg in 1822, along with the couple’s nine children at the time.

Eliza "Liza" Nebbit (sometimes spelled Nibbit or Nesbit) was transferred by Bishop Louis William Valentine DuBourg to St. Rose Philippine Duchesne and the Religious of the Sacred Heart.Photo Credit: Photo courtesy of Society of the Sacred Heart, United States – Canada ProvinceNot much is known about Harry and Jenny. Their last name is listed in records with several variations: Nebbit, Nibbit and Nesbit. But what is known is that the couple, who were enslaved for much of their lives, was purchased by Bishop Louis William Valentine DuBourg in 1822, along with the couple’s nine children at the time.

Five years later, their ownership was transferred to Bishop DuBourg’s successor, Bishop Joseph Rosati. Jenny died in Perry County in 1829; Harry is believed to have died in a tornado at St. Vincent’s College in Cape Girardeau in 1850.

One of their children, Eliza “Liza” was transferred by Bishop DuBourg to St. Rose Philippine Duchesne and the Religious of the Sacred Heart. One of their sons, Clement, was sold to Father Jean-Marie Odin, a Vincentian, who had Clement and his family sent to him in Galveston, where he would become the first bishop of the new Diocese of Galveston in 1847.

Bishop DuBourg (who at the time was Bishop of Louisiana and the Two Floridas, with his episcopal seat in St. Louis), Bishop Rosati, and Archbishop Peter Kenrick, along with an unknown number of clergy, enslaved people. To date, a list of 85 names of people who were enslaved has been compiled. That number is expected to fluctuate as records and variations in names are further researched, said Eric Fair, director of the archdiocesan Archives Office.

Among the goals of the research is to learn more about the individuals who were enslaved by bishops and archdiocesan priests. Researchers hope to eventually connect with descendants and discuss findings from examining sacramental records, financial ledgers, written correspondence, papal documents and business contracts, among other resources. Modern descendants have not yet been identified.

In a financial ledger from 1830-1839, Bishop Rosati recorded the sale of “my negro boy called Peter about nine or ten years old” to Vincentian Father John Bouiller for the sum of $150.

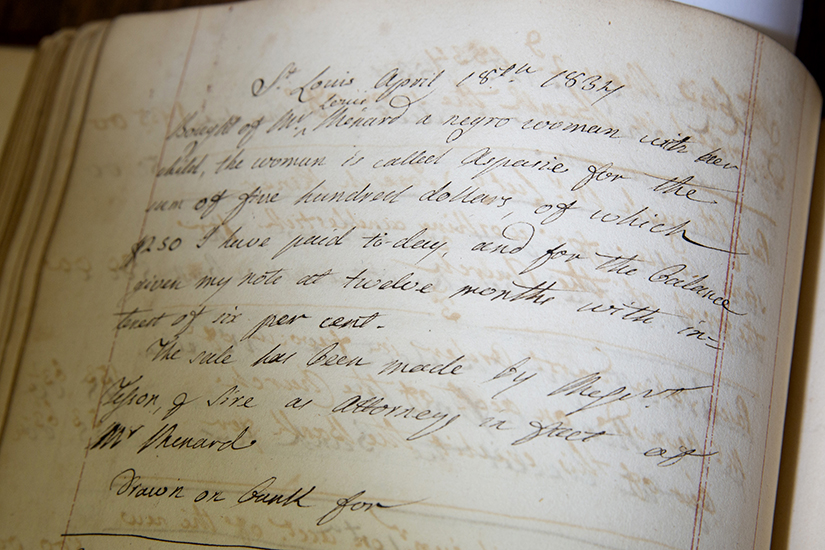

Another enslaved person, a woman named Aspasia, sued several times for her freedom, before, during and after her enslavement to Bishop Rosati. She eventually won her freedom based on her own court records, other court records from her family members and a freedom license that appears to be hers, according to researchers.

“The names of these people have always been here,” Eric said. “They’ve just been waiting for someone to tell their stories.”

Collaboration

A financial ledger of Bishop Joseph Rosati at the archdiocesan archives shows the purchase of "a negro woman with her child, the woman is called Aspasia" (sometimes spelled Aspasie).Photo Credit: Jacob WiegandArchdiocesan researchers have found overlapping of information with other religious orders who also enslaved people, such as the Society of Jesus (Jesuits), the Vincentians and the Religious of the Sacred Heart.

A financial ledger of Bishop Joseph Rosati at the archdiocesan archives shows the purchase of "a negro woman with her child, the woman is called Aspasia" (sometimes spelled Aspasie).Photo Credit: Jacob WiegandArchdiocesan researchers have found overlapping of information with other religious orders who also enslaved people, such as the Society of Jesus (Jesuits), the Vincentians and the Religious of the Sacred Heart.

For example, in a contract between the Society of Jesus (Jesuits) and Bishop DuBourg, in which the bishop gave the Jesuits responsibility over Saint Louis University, a clause was included that gave approval to bring their enslaved people to the area.

“When we talk about the past history of Catholicism in St. Louis, we’re more than happy to celebrate our successes and our joys,” Eric said. “What we don’t talk about is a lot of those successes, a lot of those joys, were on the backs of enslaved persons.”

Last year, the archdiocesan Archives Office formed CROSS, a collaboration of a dozen dioceses and religious communities that share resources and best practices within their own research efforts. Archbishop Shelton Fabre of Louisville, Kentucky, who oversees the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops’ ad hoc Committee Against Racism, advises the group.

Sin of racism

Some people still struggle with the idea of the Church’s involvement in what the USCCB have described as the “sin of racism,” Joyce said.

While not everyone at the time was on board with the idea of slavery, there were many in the Church who were — and those actions have had a lasting, multi-generational impact upon race relations in the archdiocese, especially among Black Catholics.

“People are horrified to find that the Church sanctioned” slavery, Joyce said. “The Church was one of the biggest participants in this. For African-American Black Catholics, the place where they were supposed to be able to come and lay their burdens down and talk to God was the place that was oppressing them.”

Maafa

People walked in the Maafa procession June 18 on the grounds of the Gateway Arch in St. Louis.Photo Credits: Jacob WiegandIn June, the archdiocese held a prayer service and Maafa procession to remember those who were part of the slave trade here in St. Louis. Maafa, a Swahili word for “great disaster,” is a traditional procession to memorialize the lives of those lost during the Middle Passage, or transatlantic slave trade.

People walked in the Maafa procession June 18 on the grounds of the Gateway Arch in St. Louis.Photo Credits: Jacob WiegandIn June, the archdiocese held a prayer service and Maafa procession to remember those who were part of the slave trade here in St. Louis. Maafa, a Swahili word for “great disaster,” is a traditional procession to memorialize the lives of those lost during the Middle Passage, or transatlantic slave trade.

The event included a prayer service featuring Archbishop Mitchell T. Rozanski and other area faith leaders at the Old Cathedral, followed by a procession on the grounds of the St. Louis Gateway Arch. The gathering also included a formal acknowledgment of the Archdiocese of St. Louis’ past involvement with the institution of slavery.

In reflecting on the inaugural event, Archbishop Rozanski said two words kept coming to his mind: truth and freedom.

“When we embrace the truth … can every human being created truly live in freedom,” he said. Reflecting on the past, as painful as it may be, is an important part in moving forward to change the future, understanding that every human being is created in the image of God and has a God-given dignity.

Each one of us “is given human dignity to live in freedom, to live in truth, to be able to bring that image of God into the world in such a way that our whole world is transformed,” he said.

Freedom Suits Memorial

A sculpture honoring enslaved Missourians who fought for their freedom through the courts prior to the Civil War was dedicated in Downtown St. Louis in June.

Located outside the Civil Courts building, the Freedom Suits Memorial depicts various moments from the lawsuits and the times. At the base of the 14-foot sculpture are the names of more than 300 people who asked the court for their freedom more than 150 years ago.

Before the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Dred Scott v. Sandford, Missouri’s legal system operated under a “once free, always free” policy. The courts held that an enslaved person who had been moved to a free state or territory for any length of time, then returned to a slave state or territory could sue for his or her freedom.

The Freedom Suits Memorial was installed June 15 at the east plaza of the Civil Courts Building in St. Louis. Photo Credit: Jacob WiegandJudge David Mason of the 22nd Circuit Court helped form and lead the Freedom Suits Memorial Steering Committee after the legal files of enslaved people who petitioned the court were found by courthouse employees more than a decade ago.

The Freedom Suits Memorial was installed June 15 at the east plaza of the Civil Courts Building in St. Louis. Photo Credit: Jacob WiegandJudge David Mason of the 22nd Circuit Court helped form and lead the Freedom Suits Memorial Steering Committee after the legal files of enslaved people who petitioned the court were found by courthouse employees more than a decade ago.

“It was like discovering a new vein of gold” said Mason, a member of St. Alphonsus Liguori “Rock” Church Parish. The memorial, he said, “honors their courage and bravery, the judges who upheld the rule of the law, and the lawyers and the juries who decided in favor of the enslaved person.”

Any enslaved person who sued for their freedom faced a great risk. If they lost, they were likely to suffer painful retribution or be sold “down the river” to a more brutal owner in the south.

St. Louis was an epicenter for freedom suits for nearly 60 years, from the time of the Louisiana Purchase until the Emancipation Proclamation, said Mason. The Supreme Court’s decision in the Dred Scott case essentially undid the results of the freedom suits that had been filed.

But that case changed everything — and was a step on the path leading to the start of the Civil War.